If I neglect my Google Reader for just one day, the contents build up so much that perusing them becomes more tedious than anything else. I blast through them, glancing often at only the tops of images, feeling the need to empty my “New Items” as soon as possible. I suppose I feel required to stay on top of “new things” and “new” designs — lest I become instantly irrelevant for missing a passing trend. Who knows the reason why but I surely never miss a day; my Google Reader stays empty.

Recently I read an article by one of my favorite authors, Alain De Botton. The article was called On Distraction and I found this passage of particular interest:

We are continuously challenged to discover new works of culture—and, in the process, we don’t allow any one of them to assume a weight in our minds.

I coudn’t agree more with this statement. Just think of sites like FFFFOUND, with its endless parade of sourceless and context-void images. How long do you contemplate each? Then again think of sites like this! I am as much a culprit of perpetuating this rapid culture consumption as any other blogger. I write 2-5 times per week about cool work I find, but how long do you (or I) actually spend looking at it? We glance at it, maybe visit the website, but in all likelihood it is in and out of your consciousness in less time than it took me to write the post. I’ll sometimes almost write a post on the same person twice without realizing it (this has only a few times, but is rather indicative of the problem Botton describes).

Botton’s solution to this problem is a period of culture fasting:

The need to diet, which we know so well in relation to food, and which runs so contrary to our natural impulses, should be brought to bear on what we now have to relearn in relation to knowledge, people, and ideas. Our minds, no less than our bodies, require periods of fasting.

Taking his suggestion sounds terrifying at first. It is not something I have ever been able to do by choice — usually its a vacation that puts my Reader so far over the edge that even I can’t J/K shortcut my way out — I have only hit the dreaded “Mark all as read” button a few times. It is something I would like to explore more. I remember when I grew up I was usually only aware of a few artists/musicians at one time, but I dove deep into their catalogs. My understanding of their work was broad and I can still cite examples of how whatever it was continues to influence me.

I don’t know. The article hit home for me and I am curious what you think about it all. As a blogger, I am inclined to defend my profession of endlessly posting work for the world to consume rapidly, but Botton makes a great point that seems to indicate otherwise.

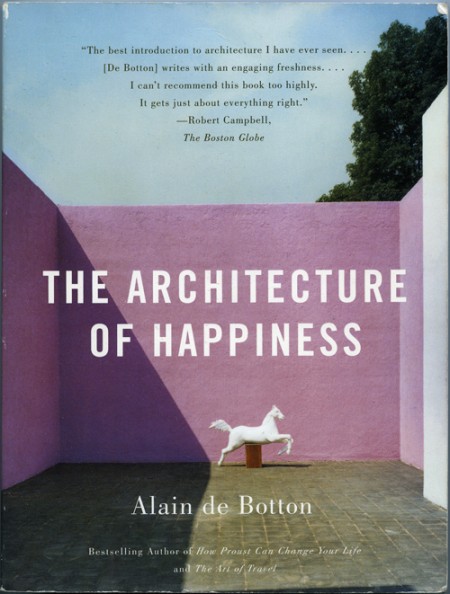

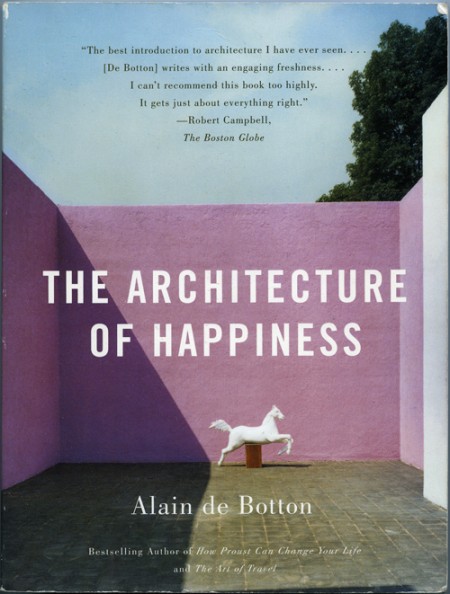

I purchased The Architecture of Happiness by Alain de Botton because I loved the cover. I think it was the colors that first caught my eye. I was also intrigued by the shadow and the shape it created; how it almost touches the statue in the most perfect way. The eye follows the line it creates, and it helps reinforce the hierarchy of the page really effectively. For whatever reason, and as the title indicates the book may elucidate, the whole design makes me happy every time I look at it.

Why this design makes me happy, and to a greater extent, why architecture of a certain aesthetic caliber appeals to us, is largely what this book explores. It is a must read for designers of all disciplines as it pursues the question at the core of what we do: Why make things look beautiful (what does “beautiful” even mean?) and not just purely functional? One of my favorite parts of the book describes the principles of some nineteenth century engineers that felt like they had determined the end-all criteria for evaluating structural design:

The engineers had landed on an apparently impregnable method of evaluating the wisdom of a design: they felt confidently able to declare that a structure was correct and honest in so far as it performed its mechanical functions efficiently; and false and immoral in so far as it was burdened with non-supporting pillars, decorative statures, frescos or carvings. Exchanging discussions of beauty for considerations of function promised to move architecture away from a morass or perplexing, insoluble disputes about aesthetics towards an uncontentious pursuit of technological truth, ensuring that it might henceforth be as peculiar to argue about the appearance of a building as it would be to argue about the answer to a simple algebraic equation.

As the rest of the book unfolds, Botton examines, as eloquently as he does above, the alternative to what these engineers proposed. Why it is that we strive to make things beautiful, and what qualities beautiful work possesses. The parallels between his chosen arena of architecture, and other realms of design, are easily drawn, and make it very worthwhile for interested minds in every field. My favorite paragraph is on page 72, and does a nice job bringing together a lot of what he discusses in the book:

In essence, what works of design and architecture talk to us about is the kind of life that would most appropriately unfold within and around them. They tell us of certain moods that they seek to encourage and sustain in their inhabitants. While keeping us warm and helping us in mechanical ways, they simultaneously hold out an invitation for us to be specific sorts of people. They speak of visions of happiness. [Buy on Amazon]

– – – –

On an unrelated Note: Peter, of Buchanan-Smith, wrote in to clarify the attribution information of a previous post on designer Josef Reyes. The work presented was produced by the studio Buchanan-Smith, where Reyes works as a designer, and the post has been updated to credit the work to the Buchanan-Smith studio. Definitely make sure to check out their site, they have a lot of great work.